Unearthing pathology of recent rise in black lung disease

The first new pathology standards for black lung disease in over 50 years were published based on research from the University of Illinois Chicago School of Public Health. The findings will help pathologists diagnose a new, more aggressive form of the condition and may provide public health officials with additional motivation for passing stricter mining regulations.

Rates of coal workers’ pneumoconiosis, the severe respiratory condition popularly known as black lung disease, resurged in the last two decades after a steep decline in the late 20th century. Work from UIC’s Mining Education and Research Center determined that the rise is likely caused by excessive exposure to silica dust in the coal mine atmosphere, compared with the coal dust that historically put miners at risk.

“In the past, these diseases generally took decades to develop, but we’re seeing them developing in much shorter periods of time, and that it’s much more inflammatory and rapidly progressive,” said Dr. Robert Cohen, clinical professor in the UIC School of Public Health and director of the center.

Two recent papers from the center expand upon this link, with both comparing the lungs of miners from the mid-20th century with those from more recent cases of black lung disease. The studies are the first update on the pathology of black lung disease since 1971, highlighting features in lung tissue that are unique to this newer version and making pathologists aware of its changing nature in modern miners.

“In a textbook today, the teaching would be that it would take decades and decades of exposure to develop pneumoconiosis,” said Dr. Leonard Go, research assistant professor and assistant director of center. “But we’re seeing cases of disease in people with five, six years of exposure, sometimes less. And that’s almost certainly because of a more prominent silica component of contribution to their disease.”

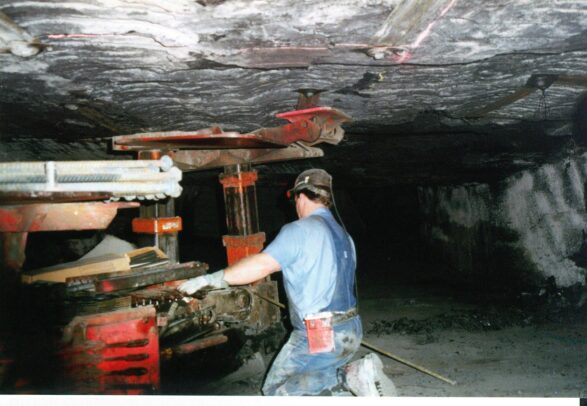

Silica dust is known to be highly toxic, causing lung damage, cancer and COPD. While exposure to the substance in most professions is already limited by OSHA regulations, coal miners — governed by a separate federal agency — are still legally allowed to inhale twice as much of the dust on the job. Modern changes in coal mining, such as increased use of heavy machinery and mining of thinner coal seams surrounded by silica, may also contribute to higher exposures, the researchers said.

In one paper, the center researchers conducted a statistical comparison of lung tissue from miners born between 1885 to 1950. The historical samples were gathered from an archive in West Virginia at the Respiratory Health Division of the National Institute for Occupational Safety & Health that the researchers discovered in the basement of the facility.

“It was almost like discovering archaeological evidence, because it has these ancient lungs from guys that were born in the early 20th century,” Cohen said. “It was kind of exciting for us, as pulmonary detectives, to find it.”

Researchers evaluated the specimens for the presence of progressive massive fibrosis, the most severe form of pneumoconiosis. They grouped each case into coal-type, mixed-type and silica-type based on the microscopic characteristics of the lung nodules.

When analyzed over time according to the birth year of the miner, the researchers found that the frequency of coal-type and mixed-type disease declined, likely reflecting the passage of stricter mining regulations. Conversely, rates of silica-type disease stayed constant, even increasing among miners born more recently.

“We saw the rise in disease, and now we can see under a microscope that the pattern of disease is clearly consistent with silica,” Go said. “It’s a smoking gun that something has to change to prevent this disease.”

In a second paper, an international panel of pathologists looked at 85 lung samples, but were not told whether they were from historical miners — those born before 1930 — or contemporary miners born after 1930. Once again, the researchers found that silica-type lesions were more common in contemporary miners than their earlier counterparts.

The analysis also offered detailed descriptions of additional features that are unique to the newer form of the disease, including alveolar proteinosis — a condition previously associated with heavy acute silica exposure but not previously observed in coal miners — and signs of inflammation and fibrosis. It also revealed the startling absence in contemporary miners of coal macules and nodules, once considered a hallmark of black lung disease.

The authors hope that this new information will aid diagnosis of the disease in its new form.

“We want pathologists to recognize this disease, to increase the knowledge and awareness of how this disease looks.” Cohen said. “We’re updating the literature so that pathologists are aware of the rapidly progressive nature and the new signs of disease.”

The authors also hope that the new findings will add more urgency to the debate around further limiting coal miners’ exposure to silica dust and lead to quicker passage of new regulations that further reduce miners’ exposure to dust particles. A federal rule bringing mining restrictions in line with OSHA standards is currently under consideration by the Mine Safety and Health Administration.

“We’re hoping that the studies will add more urgency to this issue and help the agency get this rule out,” Cohen said.