Undergraduates get lesson on diet, memory

How is your memory affected by the food you eat and the bacteria in your gut?

How is your memory affected by the food you eat and the bacteria in your gut?

Although the connection between the gut, brain and mouth may seem a little stretched, the neurobiological links of diet and the gut microbiome to cognitive function have been the subject of research of Scott Kanoski, assistant professor of biological sciences at the University of Southern California, for the past six years.

Kanoski spoke about his research at the 10th Annual Chris Comer Undergraduate Neuroscience Symposium. The series is held in honor of former UIC professor Chris Comer’s tremendous contributions to science education, including the development of the first undergraduate neuroscience program in Illinois.

Kanoski uses rat models in highly controlled experiments to understand the biological effects and mechanisms of an unhealthy diet. The rats are subjected to dietary manipulations during juvenile and adolescent periods of growth in which the hippocampus develops.

The hippocampus is primarily responsible for the brain’s integration of memories for long-term storage. It also plays a role in inhibiting excessive food intake through the detection of internal hunger and satiety signals.

“Disrupted hippocampal-dependent memory process are linked with Western diet consumption,” Kanoski said.

With the administration of both a complete Western diet and added sugar in isolation, the rats experienced hippocampal dysfunction as revealed by difficulty in tasks related to discrimination reversal learning, spatial working and reference memory.

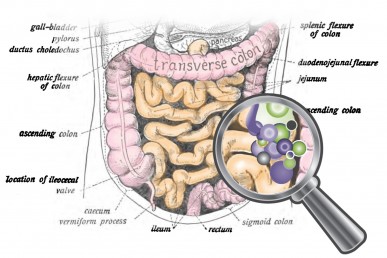

Sugar consumption had a significant impact on the integrity of the gut microbiome, which is the aggregate of about 100 trillion microorganisms that reside in the gastrointestinal tract.

The result is a “viscous circle,” in which the consumption of an unhealthy Western diet during adolescence impacts the hippocampus and the gut microbiome to product deficits in memory and internal satiety cues later in life. The gut microbiome and hippocampus are interrelated so that changes in the former negatively contribute to hippocampal activity.

These cognitive impairments occur independent of obesity.

“Dietary factors can impact hippocampal function without producing full-blown metabolic deficits,” Kanoski said.

Simple dietary intervention is not enough to reverse the deficits caused by an excessive consumption of sugar in the critical juvenile developmental stage, Kanoski added. However, research into other potential repair mechanisms, such as exercise, could provide further insight into these processes.

Magdalena Maani, a senior in biology, attended the event as part of her neuroscience course. Apart from being a requirement, however, the seminar attracts students who are interested in the latest developments in neuroscience.

“I personally did want to attend,” said Maani, “because instead of just focusing on theory from the textbook, I wanted to learn about what topics a current neuroscientist is researching about in the present.”