UIC researchers part of NASA team exploring Jupiter moon

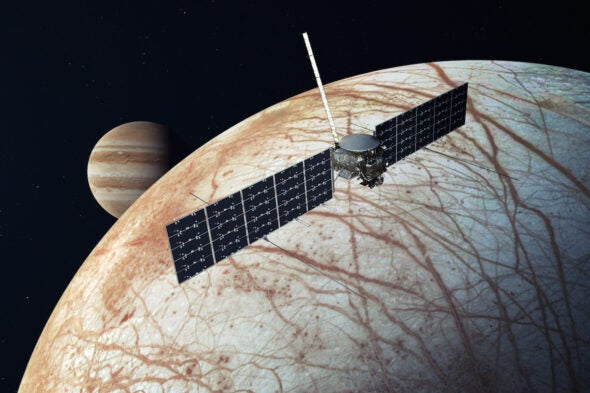

Last week, the Europa Clipper spacecraft began its six-year flight to Jupiter’s moons — and University of Illinois Chicago faculty and students will play a key role in its 1.8-billion-mile journey.

Andrew Dombard, professor of planetary science, geophysics and planetary exploration at UIC, is part of the gravity/radio science team for the NASA mission to Jupiter’s moon. For the last four years, he has helped prepare mission experiments to look for life-supporting geological features on the moon’s sea floor.

Since the discovery of ice on its surface in the 1950s, Europa has fascinated scientists because it may have many of the conditions necessary for life to form. Previous spacecraft fly-bys have confirmed further details, such as a subsurface ocean and possible erupting water plumes, that could support Earth-like biological systems.

“Europa is one of the prime candidates for extraterrestrial life elsewhere in our solar system,” Dombard said. “In order to start answering questions about whether we are alone in the universe, we need to go assess the habitability of Europa.”

Unlike with the other experiments on the mission, the gravity/radio science team didn’t need to design a new instrument for the 13,000-pound spacecraft. Instead, Dombard and his colleagues will measure frequency shifts in the radio signal Europa Clipper sends back to Earth. These shifts are caused by changes in gravity from variations in the structure of the moon.

“We’re looking at how the gravity field of Europa tugs on the spacecraft,” Dombard said. “Every time you have a hill or a valley on a planetary surface, that represents extra mass or missing mass, so gravity varies from place to place on a planetary body.”

The scientists will look for gravity anomalies that might indicate the presence of volcanoes and hydrothermal vents, systems that are believed to have been crucial to the origin of life on Earth. They’ll also combine their findings with data from the spacecraft’s other instruments to look at structures in the ice shell on Europa’s surface.

But those analyses will have to wait — Europa Clipper will not reach Jupiter until April 2030. Until then, Dombard and his students will work with simulations that anticipate how different geological structures might change the radio signal.

One of his graduate students, Martina Caussi, is also part of the mission as an affiliate on the gravity/radio science team. Both Dombard and Caussi attended the Europa Clipper launch Oct. 14 at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

The NASA mission is an exciting opportunity for students in the UIC Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences to study geoscience through the exploration of other worlds, Dombard said.

“Planets and moons provide natural laboratories for understanding geological processes that operate throughout the solar system,” Dombard said. “While we’ve answered all the big-picture questions for the Earth, those big-picture questions still exist for the other planetary bodies. As we send new missions to collect new data, it completely changes what we think about these worlds, and it really refines what we know and what that means for here on Earth.”