Clearer picture for med students

Medical students watch a broadcast of a medical procedure done by a physician wearing Google Glass. (Photo: Vibhu S. Rangavasan)

By Jackie Carey and Sharon Parmet

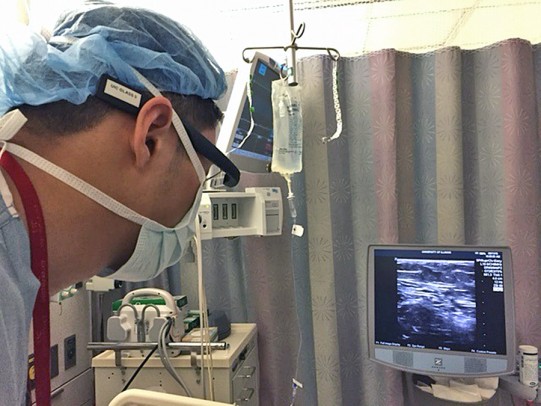

Chad Lee, a resident anesthesiologist at UI Health, watches intently as his colleagues, led by Christopher Chiang, associate professor of clinical anesthesiology, perform an ultrasound-guided femoral nerve block to numb the leg of a patient who has just received knee replacement surgery.

As Chiang threads a thin tube into the space next to the femoral nerve of the woman, Lee watches its progress into the woman’s leg on an ultrasound screen, which, to the untrained eye, looks like layers of a black, white and gray lasagna.

And that’s the point — to begin to train the untrained eyes of first-year medical students.

Lee is wearing Google Glass, a pair of glasses that includes a tiny camera, speaker and microphone that picks up whatever Lee is seeing, saying and hearing. The glasses broadcast to a remote screen, in this case the new College of Medicine Learning Center, where more than 200 first-year medical students were having their orientation.

Christopher Chiang wears Google Glass, glasses that have a tiny camera, speaker and microphone, in the operating room. — Photo: Sharon Parmet

“Google Glass allows first-year medical students to see things that they normally wouldn’t see until they are much farther along in their training,” said Bellur S. Prabhakar, professor of microbiology and immunology and associate dean for technological innovation and training in the UIC College of Medicine. “Using Google Glass to provide clinical experiences earlier can help students decide sooner what they might want to specialize in instead of waiting until they are in their M3 or M4 year.”

Hokuto Nishioka, assistant professor of clinical anesthesiology, stands at the front of the learning center and looks up at the screen showing the regional anesthesia procedure. Nishioka alternates between speaking directly to Lee — “Dr. Lee, can you tell us what we are looking at now?” and “Chad, can you get closer to the ultrasound?”— and addressing the group of M1 students.

“This patient just had knee surgery and we hope that this procedure will allow her to go home with as little pain as possible,” Nishioka explains to the class. “As you can see, the patient is not in a particularly spacious area, but with the Google Glass technology, all of us in the room can essentially be there without causing undue stress on her.”

The students are on the final day of a three-day orientation, and after nearly three hours of presentations they visibly perk up. They ask questions about the patient, the procedure and about the specialty. Many of these questions are answered directly by Lee.

Jillian Garcia, a first-year medical student from Hartford, Connecticut, who is interested in geriatric medicine, said the demonstration was fascinating.

“At that point I was on my third cup of coffee,” Garcia said. “When the demo came on I was completely awake, alert and present. This demo is something I’m going to remember always.”

Before medical school, Garcia spent nine years as an inner-city elementary school teacher. As a former educator and a newly enrolled student (working on her third degree), she said the idea of using technology in new ways appeals to her.

“I am a huge technology buff and the implementation of this technology in the classroom was a great way for me to gain experience with a different specialty and not have to be there physically.”

The procedure was particularly interesting to her because it’s one she has experienced as a patient.

“This procedure was great because I’ve actually had two knee surgeries and have had a nerve block — it was really cool and exciting to be awake this time and see the procedure from this perspective,” she said.

Another M1 student, Clarence Calhoun, said the demonstration was helpful because he plans to pursue a career in anesthesiology.

“I was excited to see first-hand — well, second-hand, I guess, but it feels like first-hand — what the profession offers patients,” said Calhoun, who is from Bloomington, Illinois. “This gives me a more direct look into the procedure and the experience of the patient. It’s only orientation and I’ve already learned just from observing.”

Prabhakar said Google Glass will be used for medical education this year in four areas: pathology, where it will let an instructor project what he is seeing through a microscope onto a screen in a remote classroom; cardiology, where it will help students get a better view of what an instructor sees as he works with Harvey, a medical mannequin that produces realistic heart sounds; neuroscience, where a student in the back of a group may not be able to see the procedure clearly; and the emergency department, where the technology will allow students to watch certain procedures from their classrooms, laptops or devices, without interfering with the patient care.

Prabhakar expects Google Glass to be used by more departments for both education and even patient care in the University of Illinois Hospital in the coming months.

“The use of this technology will certainly become more integrated into our medical education curricula, but for now, we are just starting to explore the possibilities,” he said.