$2.4 million NIH grant brings tropical disease vaccine closer to human clinical trials

A $2.4 million grant from the National Institutes of Health is helping UIC researchers move closer to clinical trials for a vaccine to prevent elephantiasis, a disfiguring mosquito-borne illness.

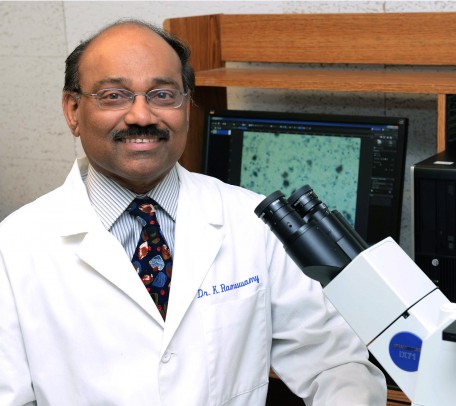

The three-year grant will facilitate a crucial step in a decades-long quest by Ramaswamy Kalyanasundaram, professor and head of the College of Medicine Rockford’s Department of Biomedical Sciences, to create the first vaccine for lymphatic filariasis, commonly known as elephantiasis, which affects more than 100 million people globally.

Ramaswamy and collaborators in Seattle received the grant from the NIH Small Business Innovation Research program. It will allow them to complete the final studies needed for investigative new drug approval from the Food and Drug Administration, so they can start testing the vaccine in humans.

“We’re hoping that in the next three to five years, the vaccine should be ready for actual human immunization,” Ramaswamy said. “I’ve had several postdoctoral research associates and graduate students work on the project over the past 20 years. All of our work is finally coming to fruition.”

Lymphatic filariasis is a parasitic disease transmitted by mosquitoes in tropical regions of Asia, Africa and parts of the Caribbean and South America. According to the World Health Organization, it affects over 120 million people in 72 countries. It is a leading cause of permanent disability worldwide, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and communities often shun and reject people disfigured by the disease.

Ramaswamy started his research in the 2000s as part of the WHO Genome Project. He identified the parasite genes that manipulate the host’s immune system to evade the immune response and survive in the human body. Later, his research group at the UIC Health Sciences Campus-Rockford identified the vaccine antigens by finding which antibodies in the blood of naturally immune people protected against the parasite’s genome.

With both approaches, they identified potential targets for developing a vaccine and have tested versions in preclinical studies over the past two decades. Through an earlier NIH Small Business Innovation Research grant, PAI Life Sciences in Seattle helped scale up production of the current vaccine formula: a combination of three antigens to induce a prolonged immune response that wards off infection. The new grant will fund toxicology studies and other final steps required for the FDA’s approval to start clinical trials in humans.

A vaccine is desperately needed, Ramaswamy said, because medications for lymphatic filariasis have failed to thwart the disease. Despite a global effort to distribute medication to areas where the disease is endemic, infections are still an issue in many parts of the world. Ten years ago, Ramaswamy spent five months in India on a Fulbright scholarship studying the effectiveness of the program and found many adults and children still suffering from the disease.

“There’s medicine available, but the medicine does not completely cure the infection and not everyone has access to or will take the drugs,” Ramaswamy said.

With a vaccine, a single shot could provide immunity for at least a year, as opposed to medicine which needs to be taken more frequently.

“If we have a vaccine, wherever you suspect that not everybody is taking the medication, you can at least give a shot and then they will be protected for at least a year,” he said.

In addition to the current lymphatic filariasis vaccine, Ramaswamy’s group is developing an mRNA vaccine – similar to those created to prevent COVID-19 infections – and a related vaccine that can prevent heartworm in dogs.

In 2020, the UIC Office of Technology Management named him Inventor of the Year, and he became the Michael L. and Susan M. Glasser Professor of Rural Health Professions Education and Research in 2023.

Carrie Foust contributed to this article.