UIC theatre students learn how to tell stories through accents

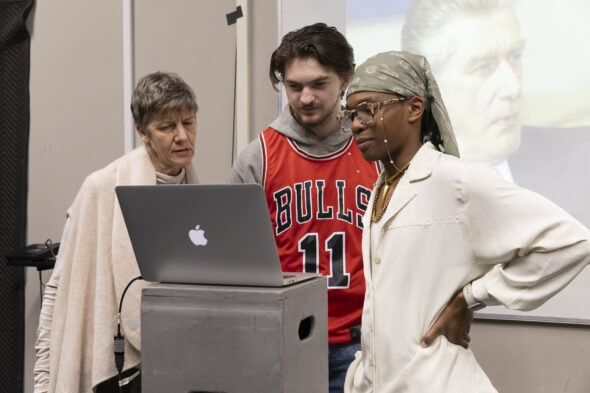

Anyone walking into Tanera Marshall’s accents class at the University of Illinois Chicago might think they’ve entered a linguistics course. In her classroom, the study of speech and accents comes down to discussions of the tongue, lips, jaws and soft palate.

Marshall, associate professor in the School of Theatre and Music, has taught UIC students voice and accents since 2004 while also coaching professional actors on how to sound like anyone from a native Chicagoan to an English aristocrat.

If you’ve seen the Chicago-based series “The Bear” or “Chicago Fire” or the Wes Anderson movie “Asteroid City,” you’ve seen Marshall’s work. Her many clients include Ebon Moss-Bachrach (“The Bear”), Eamonn Walker and Jesse Spencer (“Chicago Fire”) and Jason Schwartzman (“Asteroid City”).

In a recent talk as part of the SparkTalks series at UIC, Body and Soul: Storytelling in Accents, Marshall said that as an accent coach, her job is to help the actor tap into what she calls “the soul of the accent.”

To serve the story behind the character, accents must be true, she said. Every accent is unique — it reflects a person’s culture, ethnicity, geographical upbringing and even occupation, Marshall said.

“Simply put, an accent tells the story of a life,” Marshall said. “The soul of an accent helps us create the soul of the character. And so, whether I’m creating over-the-top characters for ‘Fargo’ or a much more realistic one for ‘The Bear,’ I explore an accent with great respect, seeking to hear the story of the life behind it.”

At UIC, Marshall’s class is required for theatre majors. They must be ready to speak in a far-flung accent at a moment’s notice and sound authentic enough to pass as a native. Marshall tells students the chance of landing a role “triples and quadruples” if they can speak with an authentic accent.

It’s a message the theatre students understand. Amy Guynn, a student in Marshall’s class, knows that being able to honestly capture an accent can make a difference in her career.

“Learning accents will give me more opportunities and expand my range and give me another tool in my actor’s toolbox,” Guynn said.

To coach both her clients and her students, Marshall uses recordings of native speakers whose backgrounds closely resemble that of the character being portrayed. For example, for the movie “Widows,” she helped English actress and singer Cynthia Erivo capture the accent of a Black female Chicagoan by using audio recordings of Ameena Matthews, a Black Chicago-based anti-violence activist.

In class recently, Marshall’s students studied a variety of New York accents, which included a Bronx accent, a Long Island accent and even a “Nuyorican” accent.

Their assignment: to find video and audio samples of native New Yorkers speaking, mimic their words and dissect how their mouths, tongues and soft palates — the back of the roof of the mouth — felt as they attempted to mirror the native speaker.

The students then had to prepare a presentation on the “oral posture” of their sample. The oral posture encompasses how the tongue sits, the jaw is held, the lips are placed and even how the upper and lower teeth may be visible as the person speaks.

For many actors, dissecting the oral posture and the rhythm and intonation, or pitch, of a person’s voice can be the most troublesome.

During class, Dan McLawhorn, a theatre major, came armed with audio and video examples of two Bronx accents.

McLawhorn played a recording of a Bronx man with an Italian background discussing growing up near Yankee Stadium. Then he played a videotaped interview with the actor and comedian Richard Mulligan, who had a pronounced Bronx accent and, like McLawhorn, was of Irish descent.

“The tongue rests on the bottom, and it’s relaxed there,” McLawhorn explained to the class while pausing the recordings. “With the lips, there is a high range of motion, but what I noticed in the Richard Mulligan interview, the corners [of his lips] were not really spread out. But on certain vowels like in ‘life,’ he would [spread them] out.”

Marshall said when students break down the oral posture of the mouth, they can get a feel of the mechanics underlying the accent and replicate them when they need to.

“The oral posture is always really weird to form your mouth in a different way; you go out of your comfort zone when you do that,” McLawhorn said.

Mila Sweeny said the most difficult part of the assignment was breaking down the oral posture and understanding the nuances behind the accents. She recalled having to navigate around an English accent recently in class.

“When we were doing the British accent, I had to continuously get my mouth in the right shape, so that was sort of challenging for me because my mouth spreads a lot,” said Sweeny, a theatre major.

Jazz Jabulani, a theatre major, chose a “Nuyorican” accent and focused on how the speaker’s words were framed by his jaw and lips, emphasizing consonants over vowels. He noted the speaker’s “hesitation” sounds that were part of the accent.

“The big thing I noticed from this is the oral posture and the hesitation sound that taught me a lot about how the jaw sits and that most of my vowels come from that,” Jabulani said. “That’s such a beautiful accent that I hope to keep learning about.”