UIC students, professor build model of world’s longest suspension bridge

When it’s completed, the Messina Strait Bridge will connect the island of Sicily to Calabria on the mainland of Italy and be the world’s longest suspension bridge at more than 2.2 miles. That’s nearly twice as long as the 1915 Çanakkale Bridge in Turkey, which holds the record as the longest suspension bridge with a span of just over 1.2 miles.

The estimated cost to build the Messina Strait Bridge is nearly $5 billion, but the ambitious engineering project is controversial for another reason: critics maintain the bridge is a risky undertaking in an active seismic zone.

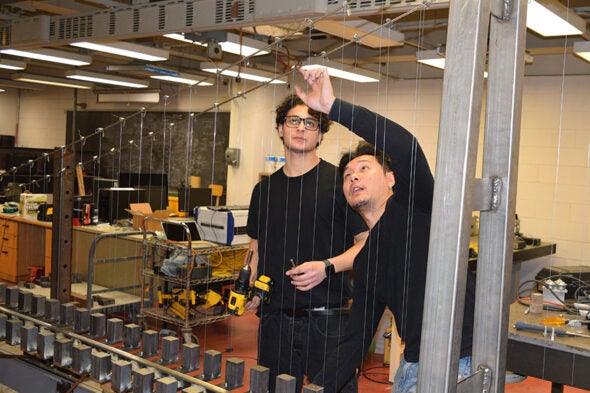

In an effort to understand how earthquakes will impact the bridge, UIC Distinguished Professor and Christopher B. and Susan S. Burke Chair in Civil Engineering Farhad Ansari and his team built a model of the bridge and plan to conduct experiments to understand how the real bridge may react to earthquakes.

The idea to investigate the Messina bridge came to Ansari while he was in Italy on a sabbatical and researching the 2018 Morandi Bridge collapse in Genoa, Italy, that killed 43 people. While gathering data from different ministries and sources, he came across the Messina bridge proposal.

“I thought since this is going to be the largest suspension bridge ever built and it has a lot of issues, it would be good to collaborate with professors from the Polytechnic University and their students and conduct experiments before construction begins,” Ansari said. “This research is going to be very useful for the actual bridge as it’s being built.”

Ansari’s team is made up of instrument and measurement technician Todd Taylor, UIC doctoral student Chengwei Wang, graduate students Salvator Marrocco and Kevin Visaggi and professor Gian Paolo Cimellaro from the Polytechnic University of Turin, Italy. Marrocco and Visaggi recently completed a six-month fellowship at UIC to pursue their thesis — which included constructing the model bridge — and recently returned to Italy, where they will continue investigating the results of their experiments.

Before building the model, the team collected data from official documents and prepared drawings and scaled down the real bridge dimensions to fit in the laboratory.

“The model is on a 1:265 scale with the dimensions, dynamic properties and the way it shakes,” Ansari said. “We will shake it the same way the actual bridge shakes, using data of actual earthquakes from that region plugged into our shaker system to see how it damages the cables and how it affects the bridge.”

“We want to remove some suspenders, which are the main cables attached to the deck, from the bridge and study the damage on the structures,” Marrocco added.

In addition to the cables, the team will investigate the bridge’s dynamic response to the soil’s changing stiffness during the earthquakes. They will do this with springs that can simulate the soil characteristics.

“My objective is to understand the behavior of the bridge under earthquake loads in undamaged conditions and varying soil conditions,” Visaggi said. “The goal is understanding the structural behavior, changing condition scenarios and validating results of the experimental analysis with the numerical model.”

The research is vital for the integrity and security of the bridge and everyone using it, the team said.

“This is one of the largest suspension bridges in the whole world, and it is very, very complicated because it’s crossing the sea, and a lot of the foundation properties are significant, especially in those places located at an earthquake zone, which is one of the most important risks of this bridge,” Wang said. “We want to research it to make sure this bridge survives. We want to know the performance of this bridge under different earthquake scenarios to get an idea of how to make the structure safer.”

“This is a big project,” Marrocco said. “We did a lot of work, and I feel proud of this work. This is an Italian bridge, and I’m happy to bring this work (to UIC) so other students can learn more about it.”

— By David Staudacher, College of Engineering