Research experience, plus a paycheck

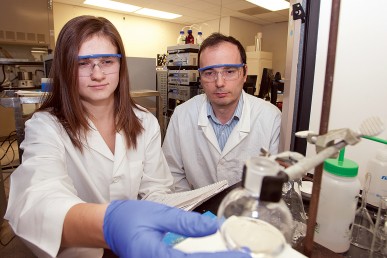

Randy Boley, left, a junior in psychology and pre-occupational therapy, and Precious Marie Walker, right, a senior in psychology and pre-med, work with Roberta Paikoff Holzmueller, center, associate professor of psychology. Photo: Roberta Dupuis-Devlin/UIC Photo Services

Michelle Vierra has had plenty of traditional college student jobs: waitress, pet store clerk, gym attendant.

But her latest job — conducting psychiatry research at UIC — has been the most rewarding.

“It’s 10 times better than any job you would get as a college student,” said Vierra, a senior in biological sciences.

“It gives you a lot of perspective and steers you in the right direction of where you want your future to go.”

Vierra is one of more than 100 UIC undergraduates who received the Chancellor’s Undergraduate Research Awards this semester.

The program, started by Chancellor Paula Allen-Meares, provides work-study funding for undergraduates to conduct research on campus. Federal work-study guidelines provide up to $3,000 per academic year for eligible students.

To be eligible for the award, undergraduates must develop a research project and collaborate with a faculty member, or join a faculty member’s ongoing research. Students can browse the Undergraduate Research Experience website and connect with researchers whose projects fit their interests.

Michelle Viera studies the genetic predisposition for depression with Monsheel Sodhi, researcher in pharmacy practice and psychiatry. Photo: Roberta Dupuis-Devlin/UIC Photo Services

Faculty members must nominate students for the award, said Thomas Moss, director of undergraduate programs in the Office of the Vice Provost for Undergraduate Affairs.

Applications are accepted throughout the year and awards are granted on a rolling basis as funding is available, Moss said.

“In some cases, students wouldn’t have been able to attend college without the financial support,” he said.

“For faculty, it gives them a deeper understanding of the quality of undergraduates who are here.”

Helping reduce rate of suicide

Vierra studies the expression of the ADAR genes in psychiatric illness, with the ultimate goal of discovering targets for new drugs to treat these disorders.

“My research gives me real-life applications for my studies,” she said.

She works in Monsheel Sodhi’s lab, which is trying to pinpoint the genetic predisposition for schizophrenia and depression, with the aim of reducing the incidence of suicide. The group, which receives funding from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, is examining postmortem brain tissue from psychiatric patients.

“We know that depression is inherited, so our research focuses on genetics,” said Sodhi, assistant professor of pharmacy practice and an Honors College faculty fellow. “If these specific genes are dysregulated in psychiatric disorders, perhaps these genes or their expression need to be the new drug targets.”

There are no cures for schizophrenia and depression, Sodhi said.

“If you take any psychiatric drug or therapy, it’s just going to manage the symptoms rather than provide a cure, and in a proportion of patients, you can’t event manage the symptoms,” she said. “It’s pretty devastating, not just for the patients, but for their entire family.”

Vierra, who wants to be a medical scientist, connected with Sodhi through the Undergraduate Research Experience website.

“I really love how research driven UIC is — it’s a really great learning environment,” Vierra said.

Sodhi has benefitted from the mentorship, too.

“I was very fortunate that the first undergraduate student (Vierra) who walked into my office after I arrived at UIC and was starting to build a research team turned out to be so great,” she said.

“It’s just such a pleasure to work with undergraduates. It’s our mission that they succeed in their career goals, but it’s even better if they are motivated to pursue a career in research after working with us.”

Researcher Roberta Paikoff Holzmueller and Precious Marie Walker study physician interaction. Photo: Roberta Dupuis-Devlin/UIC Photo Services

Learning how to talk to patients

Precious Marie Walker observes physicians in action, so she can learn how to talk to her own patients someday — not talk down to them.

She’s working with researcher Roberta Paikoff Holzmueller to analyze how doctors work collaboratively with one another, rather than taking an authoritarian approach, when determining what’s best for their psychiatric patients.

Walker observes meetings between physicians at Alivio Medical Center — some in person, others recorded.

“I watch their body language and whether they are participating in the conversation,” said Walker, a senior in psychology and premedicine and the Honors College.

“I see if doctors are over-talking or if they are open to listening to what the other doctor is telling them.”

What she’s learned is that a collaborative spirit trumps an authoritarian approach.

“Patients are more willing to adhere to suggestions if you are collaborative, so they feel like they are part of the process,” Walker said.

“I’m learning what collaborative methods I could share with other doctors to show them how they should facilitate meetings with their peers.”

Holzmueller helps Walker review the taped meetings and discuss the physicians’ behavior.

“Whenever you can help students come up with a project and see it through, start to finish, is extremely gratifying,” said Holzmueller, associate professor of psychology in psychiatry and Honors College faculty fellow.

“Students learn so much about critical thinking and the scientific method.”

The research experience is helping Walker on the way to her ultimate goal: MD/MPH degrees and a career in obstetrics and gynecology.

“The job teaches me discipline because I have to balance the research and writing in addition to all of the other classes I am taking,” she said.

“It provides me with insight into the world of medicine and great connections.”

Pinpointing when and why rehab works

Randy Boley’s research interests are sparked by personal experience with disability.

Two years ago, he could barely walk as a result of an accident that left him with spinal and nerve injuries.

“During my time in rehabilitation, I kept thinking about the reasons why it wasn’t working for some and it was working for others,” said Boley, a junior in psychology and pre-occupational therapy and the Honors College.

“It boiled it down to possibly being the result of individual personality characteristics.”

Boley is working with Holzmueller to find a link between personality characteristics and the likelihood of successful rehabilitation after a serious injury.

“I want to develop this information to see if we could start to tailor rehabilitation programs for the patient to increase the likelihood of functional outcomes,” he said.

“Maybe the person has a more conscientious attitude and is thinking about it all the time. Or maybe group therapy would be more appropriate for the patient.”

Boley is developing his research design and collecting information on patients with spinal injuries and those who have had limbs amputated.

He will also examine successful outcomes for wounded members of the U.S. military, Holzmueller said.

“We’re really interested in understanding what makes it easier to adjust to losing a limb or suffering some other sort of injury as a result of combat or accident,” she said.

Boley plans to continue his research beyond his undergraduate studies.

“There’s very little information out there so I can contribute something new that could have future clinical implications,” he said.

“There are so many variables so I can research it for a long time.”

Searching for new drug therapies

Tamara Cisowska started her pharmacy research in Dejan Nikolic’s lab over the summer, but now she’s getting paid for it, thanks to her research award.

“I wasn’t looking for awards — I just wanted the research experience to see what it’s like working in a lab,” said Cisowska, a junior in chemistry and the Honors College. “It’s nice to apply the knowledge you have in school in a real-world setting.”

Tamara Cisowska works in the mass spectrometry lab with Dejan Nikolic, faculty member in medicinal chemistry and pharmacognosy. “I wanted the research experience to see what it’s like working in a lab,” Cisowska says. Photo: Roberta Dupuis-Devlin/UIC Photo Services

Cisowska works in the mass spectrometry lab in the College of Pharmacy, analyzing plants to develop new drugs.

Using a mass spectrometry machine, she determines the mass of the compound she’s synthesizing.

“We match the mass spectrums of these plants to the compounds that are known to be in the plants,” Cisowska said.

“After we determine the compound, we can do tests on them to see how they would work in the body to see if we could possibly make a drug out of it.”

The lab is part of a bigger project — the Center for Botanical Dietary Supplements Research, which is looking for treatments for menopausal symptoms, Dejan said.

Mentoring students “does require a lot of time, but the rewards are great,” said Dejan, research assistant professor in medicinal chemistry and pharmacognosy.

Cisowska also works with graduate students and post-doctoral students in the lab.

“Talking to them and looking at some of the projects they’re doing makes me want to step up my game,” she said.

Giving people a voice

Marta Aguila wants to share the histories of those whose voices often remain unheard.

She’s creating a toolkit to help individuals or community groups share their oral history through the History Moves project, led by Jennifer Brier, associate professor of gender and women’s studies.

The project — now in its conceptual stage — involves a museum on wheels that allows people and community groups to share their stories, Aguila said.

Marta Aguila collaborates with researcher Jennifer Brier on History Moves, an oral history project. Photo: Roberta Dupuis-Devlin/UIC Photo Services

“We’re making it up so groups can set up their own oral history projects, and the curation and display of it,” said Aguila, a senior in urban planning and public affairs and the Honors College.

The History Moves project is based on the idea of engaging diverse communities across the city, Brier said.

“History really has an incredible power for people who don’t feel like their history is often told,” she said.

“Once something is located in a very specific place in Chicago, it closes off people’s access. The mobile portion of the project is both a vehicle for training people and encouraging people to develop skills in historymaking.”

When faculty work closely with students, it allows undergrads to see what a career in research is really like, Brier said.

“It shows that even if you don’t become an academic, there’s a way in which you can incorporate research into work outside the university, as well,” she said.

Although her research interests differ widely from some other students in her field of study, Aguila said, that isn’t a barrier.

“UIC allows you to research anything you have an interest in — you just have to find the professor who will fit that need,” she said.

Categories