Paleontologists flip the script on anemone fossils

Billions of sea anemones adorn the bottom of the Earth’s oceans — yet they are among the rarest of fossils because their squishy bodies lack easily fossilized hard parts. Now a team of paleontologists has discovered that countless sea anemone fossils have been hiding in plain sight for nearly 50 years.

In a newly published paper in the journal Papers in Palaeontology, University of Illinois Chicago’s Roy Plotnick and colleagues report that fossils long-interpreted as jellyfish were anemones. To do so, they simply turned the ancient animals upside down.

“Anemones are basically flipped jellyfish. This study demonstrates how a simple shift of a mental image can lead to new ideas and interpretations,” said Plotnick, UIC professor emeritus of earth and environmental sciences and the study’s lead author.

The fossils come from the 310-million-year-old Mazon Creek fossil deposits of northern Illinois. Mazon Creek is a world-famous Lagerstätte, a term used by paleontologists to describe a site with exceptional fossil preservation. An ancient delta allowed the detailed preservation of the Mazon Creek soft-bodied organisms because millions of anemones and other animals were rapidly buried in muddy sediments.

“These fossils are better preserved than Twinkies after an apocalypse. In part that’s because many of them burrowed into the seafloor as they were being buried by a stormy avalanche of mud,” said study co-author James Hagadorn, an expert on unusual fossil preservation at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science.

By far the most common fossil at Mazon Creek is the form known to local recreational fossil collectors as “the blob,” according to Plotnick, who notes that such blobs were so common and often nondescript that many were discarded or sold for a few dollars at local flea markets. Nevertheless, avocational collectors donated nearly all of the specimens in museum collections.

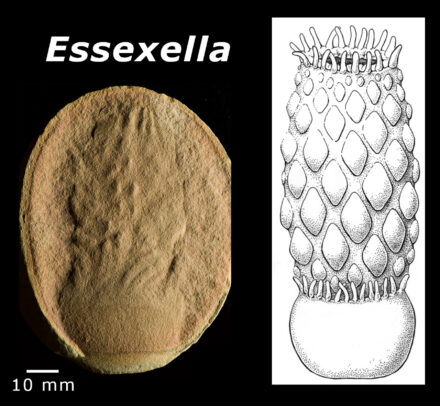

In 1979, Bradley University professor Merrill Foster made the first detailed study of the blobs. He decided that they were jellyfish and named them Essexella asherae. Foster reported these jellyfish had a unique feature found in no living jellyfish. This was a tough “curtain” that hung off its umbrella-like bell — the top part of a jellyfish — akin to a skirt that enclosed their arms and tentacles, accounting for their barrel-like shapes.

Plotnick said that Foster also suggested that a small snail sometimes found in the skirt was a predator, similar to snails that prey on jellyfish in modern oceans.

In their new paper, the paleontologists took a fresh look at Essexella by examining thousands of museum specimens.

“It quickly became obvious that not only it wasn’t a jellyfish, but turned upside down it was clearly an anemone, probably one that burrowed into the seafloor. The ‘bell’ was actually an expanded muscular foot used to wiggle the anemone into the seafloor,” Plotnick said.

The tough “curtain” was the barrel-shaped body of the anemone. Another fossil jellyfish species that looked like a daisy turned out to represent rare anemones squashed from top to bottom, like one might stomp an aluminum can.

“Although most of these fossils are preserved as decomposing blobs that look like a piece of used gum on the sidewalk, some specimens are so superbly preserved that we can even see the muscles that the anemones used to bend and contract their bodies,” said study co-author Graham Young, an expert on fossil jellyfish from the Manitoba Museum.

The researchers explain that the wide variety of preservation seen in Essexella specimens was due to the different durations that dead anemones sat on the seafloor before burial. The snail was not a predator, but a scavenger on the carcasses.

“When jellies like Essexella wash up onto the beach, they become a veritable beachside buffet, being snacked on by snails and other creatures like we see in this fossil deposit,” Young said.

The team also suggested that a common trace fossil from the same period, long believed to be an anemone burrow, was made by an animal similar to Essexella. Because Essexella is so abundant, it may have lived in large aggregations on the sea floor, they report.