Gallery 400 exhibit ‘The Mask of Prosperity’ explores the deeper meaning of inheritance

As curator for Gallery 400’s group exhibition, “The Mask of Prosperity,” Denny Mwaura gathered the wide-ranging work of 11 artists to illustrate the role inheritance plays in multiple dimensions of our lives.

What do we inherit from earlier generations? It’s not just material things, but the “baggage,” Mwaura says. We inherit traditions, legacies and our location in the world.

Mwaura’s vision has been hailed by the New City Art publication as a “curatorial masterpiece” for allowing the artists to explore the notion of inheritance in a cohesive yet personal way.

In “The Mask of Prosperity,” a violin bow made from the artist’s dreadlocks is paired with a speaker playing a Black hymnal. Photos of women working in abortion clinics decades ago dramatize a debate that continues today. Three rings with sugar, cotton and human hair in place of gemstones depict the struggle of enslaved ancestors.

Mwaura, Gallery 400’s assistant director, recently spoke to UIC today about the exhibit, which is open to the public and runs until Aug. 3 at Gallery 400, 400 S. Peoria St. The following was edited for clarity.

UIC today: What was your aim as you curated “The Mask of Prosperity”?

Mwaura: I wanted to make a show that intimately demonstrates how material and immaterial inheritances can shift our lives’ trajectories. Over the past several years, I’ve been seriously considering what makes a good life. The new commissions in the exhibition attempt to answer this everlasting question. I wanted to organize a show that made private feelings public, enabling audiences to identify and reflect on how residues from the past — be it from their ancestors or socio-cultural backgrounds — determine what our definition of living prosperously means.

UIC today: What did you learn from curating the exhibit?

Mwaura: I learned that inheritance is unfinished business. It is baggage that continues to track from one generation to the next generation. There are many ways to think about inheritance. We mostly think about it from a monetary or proprietary perspective. But inheritance appears in various ways, such as social movements, where we are indebted to the people who came before us and how they have made our lives today better, or lack thereof.

I also learned how artists are deeply engaged in resisting systems that impinge on our self-determination. That ranges from racial capitalism to other exploitative systems within culture and society. I was drawn to their creative strategies in expressing inheritance’s tangible and intangible forms.

UIC today: Which are your favorite pieces in the exhibit, and why are they important to you?

Mwaura: I have many favorites in this exhibition. For one, I would say “Hairbow for Sounding the Ancestors.” It is a violin bow made by artist Sonya Clark using a dreadlock of hers, and a sound piece accompanies it. Clark asked her friend Regina Carter, who is a jazz violinist, to play the hymn “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” which is considered the Black national anthem. We are listening to this brooding, resonant soundtrack that also serves as the soundtrack of the entire exhibition. I love this piece because of its materiality in thinking about the cultural significance of hair within Black culture and the African diasporic communities. Hair is something that can tell us a lot about people. During the Middle Passage, hair was used as a conduit to bring seeds, such as okra and black-eyed peas, from Africa to the Americas. Hair was the medium that allowed Africans to continue preserving their cultural heritage.

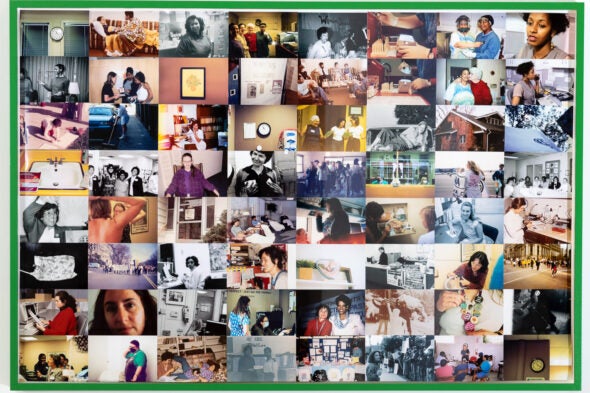

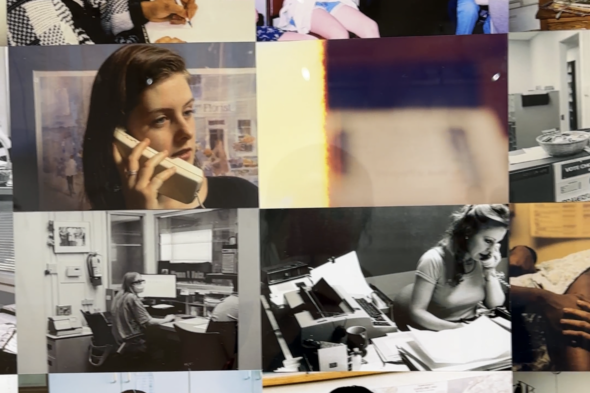

Another favorite is a collection of photographs by the artist Carmen Winant organized in a grid. These are 6-inch-by-4-inch images she collected, scanned and reprinted from various institutional archives in the Midwest and abortion clinics throughout the Midwest, including in Michigan, Illinois, Nebraska and Ohio. We are looking at women doing very ordinary tasks such as leading demonstrations, workshops and protests. Some are singing, and some are on the phone. There is a cinematic element to these images. What I love about these photographs is the attention Carmen pays to visualizing demonstrative care and what makes abortion access safe for a lot of women in the U.S., specifically. The one thing that recurs a lot is that you’ll see a lot of women on the phone, and we never know who is on the other end of the phone; it could be another woman in another state. From mass media, we often see images of abortion clinics from the outside, and Carmen inverts that by highlighting networks of care and lateral forms of kinship within these spaces.

UIC today: Can you talk about the artists connected to UIC?

Mwaura: One of the artists in the show is Nate Young, who is an assistant professor and director of graduate studies in the School of Art and Art History. This is a collaboration with his partner, Caroline Kent, who also previously taught here at UIC and is currently at Northwestern University. This is a piece they made thinking about legacies they have inherited not only as artists but also what they would like to pass down to their children. Nate is a sculptor, and Caroline Kent is a painter. This work is dedicated to their three children; hence, there are three works (panels) in the piece. Here they consider the ethics that compose their creative practice and how each panel will be entrusted to their children. It’s an important collaboration because it prompts us to think about family values and how they shift from one generation to the next.

UIC today: What do you want people to take away as they go through the exhibit?

Mwaura: Exhibitions are platforms for creative and intellectual inquiry, so I would like for our audiences to deeply think about how inheritance shapes their lives, the things they have acquired and things they have also chosen to reject. Not only in terms of capital and its accumulation but also thinking about social movements as well and thinking about systems that are in place in various parts of our lives. For example, in Carmen Winant’s work, the system in place is the Supreme Court, which has exerted its influence on women’s bodily autonomy. I also want people to consider what is it that we gain from loss.