First-year writing course increases belonging, retention at a broad-access university

Colleges and universities strive to use best practices and innovative ways to cultivate and support students’ sense of belonging, a consideration that is acutely important during the COVID-19 era.

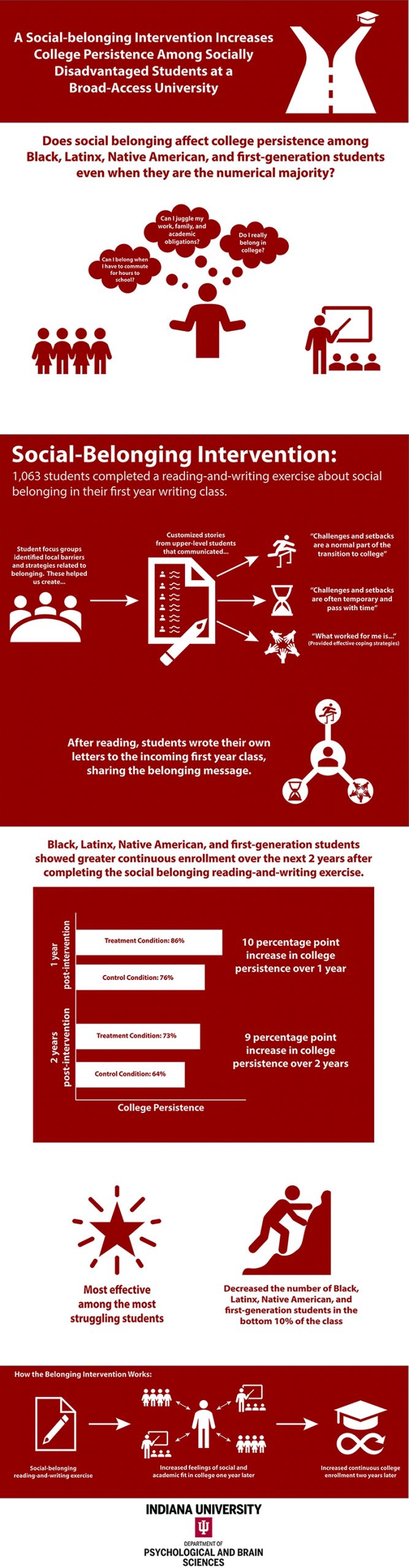

New research published in the journal Science Advances suggests a reading-and-writing exercise about social belonging is an effective strategy to help student performance and retention, particularly for Black, Latino, Native American, and first-generation students at large, urban, broad-access universities.

Co-author of the study Bette L. Bottoms, professor of psychology at the University of Illinois at Chicago, said the social belonging intervention is a unique, successful and cost-effective way to assist students in their transition to college.

“The belonging intervention was so simple, yet the effects were so important — including decreasing the likelihood that students dropped out of college two years into the future. And the students who benefitted most were those who have been historically disadvantaged,” Bottoms said. “I hope more universities will use such interventions, especially the large, broad-access universities whose mission is to create not only a more educated American society, but a more egalitarian one.”

Bottoms, along with the study’s lead author Mary Murphy, the Herman B. Wells Professor of Psychological and Brain Sciences at Indiana University, and their colleagues, conducted the reading-and-writing intervention as part of a three-year study of more than 1,000 students enrolled in first-year writing classes at large, diverse, broad-access post-secondary institutions in the Midwest.

The 50-minute social-belonging intervention was created after the researchers conducted extensive focus groups and surveys with previous cohorts of students, faculty and administrators to learn about the local barriers to belonging that students at the university faced and the strategies that were effective in helping students overcome those challenges.

The intervention required first-year students to read stories written by upper-year students about challenges that threatened their feelings of belonging on campus, such as commuting long distances and working multiple jobs. The stories “taught” that these challenges were common, normal and temporary. Then, the first-year students wrote about how their own experiences mirrored those stories, and wrote a letter to a future student who might have doubts about their belonging to college.

This encouraged students, especially Black, Latino, Native American students and first-generation students of any racial-ethnic background, with an adaptive narrative for making sense of concerns about belonging in their transition to college, according to the researchers.

The researchers assessed continuous enrollment records gathered from the university for two years post-intervention. They also conducted daily-diary surveys for nine days after the intervention, and they conducted a one-year follow-up survey to assess how the intervention affected students’ psychological experiences.

Some of the key findings include:

• The intervention improved college persistence (the rate of reenrollment the next year) by 10% one-year post-intervention, from 76% to 86%, and 9% two-years post-intervention, from 64% to 73%, for Black, Latino, Native American and first-generation students.

• Moreover, these structurally disadvantaged students were more resilient to challenges and adversities after treatment. While they still experienced the same amount of challenges and adversities as their peers in the control condition, students’ sense of belonging in the treatment condition did not fluctuate based on these challenges, as it did for their control group peers. These students’ sense of belonging was more stable and secure across the nine days of daily-diary surveys.

• Examining the long-term psychological and academic outcomes, the researchers found that structurally disadvantaged students in the treatment condition experienced greater feelings that they fit in socially and academically in college one year later and this explained their increased college persistence two years later. There were no consistent effects for continuing-generation White students.

• The academic gains were concentrated among students who struggled most in their first semester in college. And, the intervention decreased the number of structurally disadvantaged students in the bottom 10% of their class in terms of grades.

“Learning about the social and academic challenges to belonging that their peers experienced and learning about the coping strategies their peers used to navigate those challenges helped secure the students’ sense of social and academic fit in college one year later, which predicted their college persistence two years later,” Murphy said. “We were able to observe the long-term psychological process that helped explain how these social-belonging programs have their effects.”

In addition to Bottoms and Murphy, co-authors of the study include Maithreyi Gopalan, assistant professor of education at Penn State University; Evelyn Carter, director at Paradigm Strategy, Inc.; Katherine Emerson, visiting research associate at Indiana University; and Gregory Walton, associate psychology professor at Stanford University.

Funding for the study was provided by the participating university, the National Science Foundation and the Russell Sage Foundation.