Finding scientific facts in science fiction

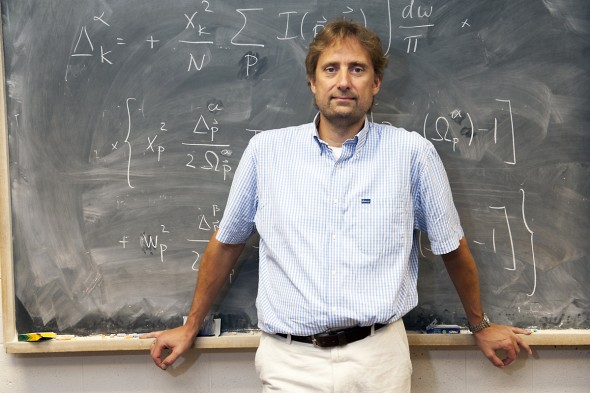

Dirk Morr’s fascination with “Star Trek” while he was growing up started him on his journey into science. “It’s a trait of scientists that we want to see what’s around the corner,” says Morr, professor of physics. Photo: Roberta Dupuis-Devlin/UIC Photo Services

Scotty emulators can’t beam anybody up — not yet, anyway — but much of what “Star Trek” showed us 50 years ago as science fiction is scientific fact today, says UIC physics professor Dirk Morr.

One example: Lt. Uhura’s earpiece, forerunner of the now-ubiquitous Bluetooth device.

Nanoprobes, which turned people into borgs on the show’s “Next Generation,” are used to save lives today, injected to “attach to cancer cells — they’re metallic so they heat up very rapidly and destroy the cells,” Morr said.

The alien translator used by Captain Kirk and crew finds its latter-day equivalent in a phone app “where you say a sentence and it’s translated into French or Spanish,” he said.

The communicator flip-device? “Our smart phones,” he said, “are much more powerful and versatile.”

Kirk also made use of a tablet that foresaw the iPad of today.

What “Star Trek” tech isn’t here yet?

Warp drive would require penetrating the wall that is the speed of light, i.e., moving even faster. Is that possible?

“The special theory of relativity tells us no, but will we be able to get through in the future? We really don’t know at the moment,” Morr said.

“But the only thing that separates us from that is a brilliant idea.”

Wormholes, on the other hand, are already known to be possible.

He demonstrates with a piece of paper. Placing the left and right edges of the paper together, Morr illustrates a wormhole, the bending of space and time for instantaneous travel.

“In 1988 at Caltech, Kip Thorne showed that you could create wormholes that would live long enough that you could move through them,” he said, although we don’t yet know how.

No less a challenge is beaming technology, which requires the conversion of mass into energy. Scotty used to beam Kirk, Mr. Spock & Co. up to the starship Enterprise every week. But to beam even a sandwich, Morr said, “would require us to store as much energy as the entire world uses in about an hour.”

How about a 12,000-pound elephant? “The energy would be equal to that of world consumption in a year, while the amount of information we needed to store would be 100 trillion times the size of the World Wide Web,” he said.

Morr talked about all this April 2 at a lecture on campus, sponsored by the Chicago Council on Science and Technology, titled “The Real Science Behind ‘Star Trek.’”

Its genesis was an exhibit called “Science Storms” that he helped create for the Museum of Science and Industry, which opened in 2010.

“They wanted to see if the exhibit could duplicate the research we were doing in our computer and labs,” he said.

Similarly, he wanted “to connect something as popular as ‘Star Trek’ with the cutting-edge research we’re doing at UIC and other universities,” he said.

“Star Trek” first aired in 1966 to 1969. It was shown in Germany, where Morr grew up, in the early ’70s when he was a kid.

“I was fascinated by the idea of jumping into a space ship and going to distant galaxies,” he said.

He earned a master’s degree at the Free University of Berlin and a Ph.D. at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, followed by post-doctoral work at Urbana-Champaign. He was a director’s fellow at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico for two years before joining UIC in 2001. He is also an associate of the James Franck Institute at the University of Chicago.

Morr lives in Chicago’s Edgebrook neighborhood with his wife, Elizabeth Elliott, professor of Slavic linguistics at Northwestern University, and their children, Leni, 8, and son, Max, 6.

A fan of literature, he recently re-read War and Peace.

How much did his early interest in “Star Trek” have to do with his trek to academic stardom?

“I would say it definitely started a fascination with science,” Morr said.

“It’s a trait of scientists that we want to see what’s around the corner. It’s why many of us become scientists.”