Exhibit tells of dark voyage

The tragedy and terror of the Atlantic Slave Trade are illuminated in a new UIC exhibit that launched its planners on a trans-Atlantic odyssey of their own.

The exhibit came together through the work of (L-R) Peggy Glowacki, Valerie Ann Harris and Nancy Cirillo. Photo: Jeff Dahlgren

By John Gregerson

It began with a 200-year-old, leather-bound volume, a first-hand account of Scottish physician Mungo Park’s 1795 expedition to Africa to locate the source of the Niger River.

A large map unfurls from the volume, one that not only charts the trajectory of Park’s travels, but the far darker trajectory of the African slave trade.

“The slaves are commonly secured by putting the right leg of one, and the left of another, into the same pair of fetters,” writes Park. “By supporting the fetters with string, they can walk very slowly. Every four slaves are likewise fastened together by the necks.”

The discovery of the hand-drawn map led three UIC scholars — Nancy Cirillo, professor emerita of comparative literature, Valerie Ann Harris, assistant professor and associate special collections librarian, and Peggy Glowacki, library reference specialist — on a two-year journey leading to a Daley Library exhibit that illuminates one of history’s darkest hours, while reclaiming library collections largely lost in shadow.

“Commerce in Human Souls: The Legacy of the Atlantic Slave Trade,” on display until May 31on the Daley Library’s third floor, pieces together artifacts from three collections — the Atlantic Slave Trade Collection, Sierra Leone Collection and Carberry Collection of Caribbean Studies — to present a picture of “a business too big to fail,” as Cirillo says, and the British Abolitionists who succeeded in bankrupting it.

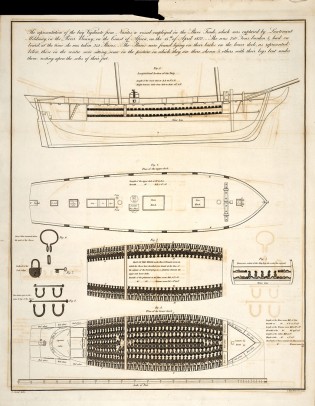

From the remnants of history, including letters, diaries and ledgers, shipping manifests, captains’ reports and ship drawings, emerges a narrative that spans from Sierra Leone to Liverpool and from Liverpool to the Caribbean.

It concludes where it began, amid the hills of Sierra Leone, where freed slaves from Britain, Nova Scotia and the United States resettled in the early 19th century, in a place named Freetown.

But this isn’t a story that comes full circle. As in Sierra Leone, the legacy of slavery lingers an ocean away in the Caribbean, amid the poverty, deprivation and illiteracy chronicled in “Commerce in Human Souls.”

The exhibit is also the story of “the legacies of prejudice and predatory economic practices, and of widespread poverty that endures to this day,” says Cirillo, who curated the exhibit.

How the tale came to be told is a story all its own, one that actually begins not with a single volume, but with hundreds purchased in the late 1960s and early 1970s by Richard Seidel, a UIC bibliographer charged with acquiring rare collections for the library.

He assembled a 700-volume book collection that charted the Atlantic slave trade, as well as another collection that included two linear feet of archival materials chronicling Britain’s burgeoning abolitionist movement.

For decades, few at UIC realized that either collection existed. In 2008, while she was familiarizing herself with uncataloged backlogs at the library, Harris found “this amazing stash of early 18th-century and late 19th-century material about the Atlantic slave trade.”

The collections struck Cirillo and Harris as curiosities.

“They seemed so out of place,” says Harris, “given that our collections focus almost exclusively on Chicago history.”

The two met with Seidel, now retired from Chicago’s Newberry Library, and learned that he’d been commissioned by UIC in the 1960s to purchase collections for the fledgling Circle Campus.

“The university opened its checkbook and told him to do something interesting for the library,” Cirillo says.

Seidel’s interests in abolition led him to Boston, New York City and Washington, D.C., as well as London, Liverpool and Bristol —“Britain’s big slave ports, as well as places you’d expect to find small, antiquarian book shops,” she recounts.

Decades later in 1997, a third collection, this one related to the Caribbean, arrived at UIC through serendipity and Cirillo’s efforts. Friends visiting the island of Nevis, near St. Kits, told a local bookstore owner of Cirillo’s interest in Caribbean literature. The proprietor told a Jamaican publisher, who mentioned the Carberry Collection, owned by H.D. Carberry, one-time nationalist poet and Appeals Court justice.

“Locals couldn’t afford to buy it and Carberry’s widow couldn’t afford to give it away,” Cirillo says.

Its 1,000 volumes include literature, history and political theory by the region’s “Boom Generation,” “the first generation of mass literacy, mostly men from places like Jamaica, places that didn’t provide its natives a formal education until the 1890s,” Cirillo says.

Two authors to emerge from the collection, Derek Walcott and V.S. Naipaul, both went on to win the Nobel Prize for Literature.

To prepare for the exhibit, Cirillo and Harris traveled to Liverpool, home to the International Slavery Museum dedicated to commemorating the Atlantic slave trade.

“What struck me was, here was a city dedicated to confronting the fact it was created by slavery,” Cirillo says. “For more than 100 years, 60 percent of all slave trade passed through Liverpool.”

From Liverpool, the two traveled to London to visit the British Library and meet with the curator of the facility’s African collection. They also visited University College.

“The trip gave us a better understanding of our own documents,” says Harris. It also laid the groundwork for collaborations among UIC and British cultural institutions.

For Cirillo, the exhibit composes a narrative of greed and terror, but also one of “great heroics” among British abolitionists, as embodied by Thomas Clarkson, ordained a priest by the Church of England.

“He wrote, ‘Someone must bring these calamities to an end,’” says Cirillo. “Rather than assume his post as a priest, he spent his time meeting with a handful of fellow abolitionists, maybe five in all, in a small print shop in London.”

In addition to founding the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, Clarkson helped achieve passage of the Slave Trade Act of 1807, which ended the British slave trade.

“Those people were amazing,” says Cirillo. “It’s absolutely [incredible] what they took on.”

Thanks to her own tireless efforts, the experiences of Clarkson and countless others — trader and slave, captain and cargo — are being told more than two centuries later.

“The captain’s manifests of the time were very precise,” says Cirillo. “You had the name of the ship, its tonnage and its cargo, which in addition to ‘fabric’ and ‘weapons,’ listed the item ‘negroes.’

“Hair-raising,” she says.

So it was. Is.

— UIC Alumni magazine

Categories