Ancient microbes in ice-sealed Antarctic lake

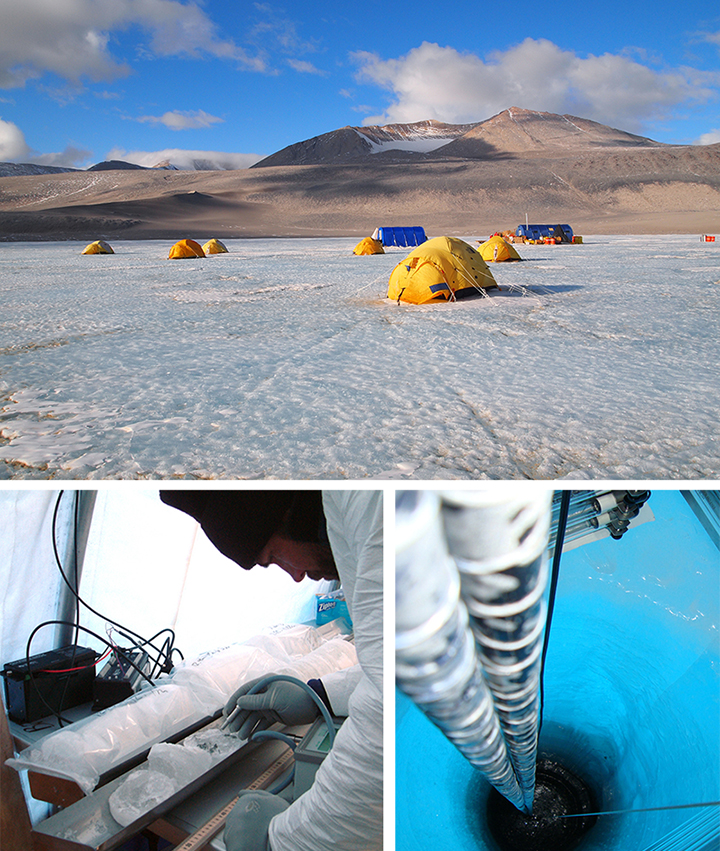

Peter Doran (from left), professor of earth and environmental sciences, Desert Research Institute research professor Christian Fritsen and ice coring and drilling services engineer Jay Kyne drill ice cores at Lake Vida in the Victoria Valley, Antarctica. Photo: Emanuele Kuhn

Shedding light on the limits of life in extreme environments, scientists have discovered abundant and diverse metabolically active bacteria in the brine of an Antarctic lake sealed under more than 65 feet of ice.

The finding, described in this week’s issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, is surprising because previous studies indicated the brine has been isolated from the surface environment — and external sources of energy — for at least 2,800 years.

“This provides us with new boundary conditions on the limits for life,” said Peter Doran, professor of earth and environmental sciences, and a co-author of the report with colleague Fabien Kenig.

“The low temperature or high salinity on their own are limiting, but combined with an absence of solar energy or any new inputs from the atmosphere, they make this a very tough place to make a living.”

The researchers drilled out cores of ice, using sanitary procedures and equipment. They collected samples of brine within the ice and assessed its chemical qualities and potential for sustaining life.

They found that the brine is oxygen-free, slightly acidic, and contains high levels of organic carbon, molecular hydrogen and both oxidized and reduced compounds.

The findings were unexpected because of the extremely salty, dark, cold, isolated ecosystem within the ice.

“Geochemical analyses suggest that chemical reactions between the brine and the underlying sediment generate nitrous oxide and molecular hydrogen,” said Kenig, professor of earth and environmental sciences.

“The hydrogen may provide some of the energy needed to support microbes.”

“We’d like to go back and find if there is a proper body of brine without ice down there,” Doran said.

“We’d also like to get some sediment cores from below that to better establish the history of the lake. In the meantime, we are using radar and other geophysical techniques to probe what lies beneath.”

The research was conducted with Alison Murray and four of her colleagues at the Desert Research Institute and 10 other scientists at other institutions.

Funding was provided by the National Science Foundation and NASA.

The camp at Lake Vida was set up on an icy surface in the Victoria Valley, Antarctica. Photos: Peter Glenday